In firefighting, fires are identified according to one or more fire classes. Each class designates the fuel involved in the fire, and thus the most appropriate extinguishing agent. The classifications allow selection of extinguishing agents along lines of effectiveness at putting the type of fire out, as well as avoiding unwanted side-effects. For example, non-conductive extinguishing agents are rated for electrical fires, so to avoid electrocuting the firefighter.

Multiple classification systems exist, with different designations for the various classes of fire. The United States uses the NFPA system. Europe and Australasia use another.

American | European/Australiasian | Fuel/Heat source |

Class A | Class A | Ordinary combustibles |

Class B | Class B | Flammable liquids |

Class C | Flammable gases | |

Class C | Class E | Electrical equipment |

Class D | Class D | Combustible metals |

Class K | Class F | Cooking oil or fat |

Ordinary combustibles

“Ordinary combustible” fires are the most common type of fire, and are designated Class A under both systems. These occur when a solid, organic material such as wood, cloth, rubber, or some plastics[1] become heated to their flash point and ignite. At this point the material undergoes combustion and will continue burning as long as the four components of the fire tetrahedron (heat, fuel, oxygen, and the sustaining chemical reaction) are available.

This class of fire is commonly used in controlled circumstances, such as a campfire, match or wood-burning stove. To use the campfire as an example, it has a fire tetrahedron – the

heat is provided by another fire (such as a match or lighter), the fuel is the wood, the oxygen is naturally available in the open-air environment of a forest, and the chemical reaction links the three other facets. This fire is not dangerous, because the fire is contained to the wood alone and is usually isolated from other flammable materials, for example by bare ground and rocks. However, when a class-A fire burns in a less-restricted environment the fire can quickly grow out of control and become a wildfire. This is the case when firefighting and fire control techniques are required.

This class of fire is fairly simple to fight and contain – by simply removing the heat, oxygen, or fuel, or by suppressing the underlying chemical reaction, the fire tetrahedron collapses and the fire dies out. The most common way to do this is by removing heat by spraying the burning material with water; oxygen can be removed by smothering the fire with foam from a fire extinguisher; forest fires are often fought by removing fuel by backburning; and an ammonium phosphate dry chemical powder fire extinguisher (but not sodium bicarbonate or potassium bicarbonate both of which are rated for B-class[clarification needed] fires) breaks the fire’s underlying chemical reaction.

As these fires are the most commonly encountered, most fire departments have equipment to handle them specifically. While this is acceptable for most ordinary conditions, most firefighters find themselves having to call for special equipment such as foam in the case of other fires.

Flammable liquid and gas

Flammable or combustible liquid or gaseous fuels. The US system designates all such fires “Class B”. In the European/Australian system, flammable liquids are designated “Class B”, while burning gases are separately designated “Class C”. These fires follow the same basic fire tetrahedron (heat, fuel, oxygen, chemical reaction) as ordinary combustible fires, except that the fuel in question is a flammable liquid such as gasoline, or gas such as natural gas. A solid stream of water should never be used to extinguish this type because it can cause the fuel to scatter, spreading the flames. The most effective way to extinguish a liquid or gas fueled fire is by inhibiting the chemical chain reaction of the fire, which is done by dry chemical and halon extinguishing agents, although smothering with CO2 or, for liquids, foam is also effective. Some newer clean agents designed to replace halon work by cooling the liquid below its flash point, but these have limited class B[clarification needed] effectiveness.

Electrical

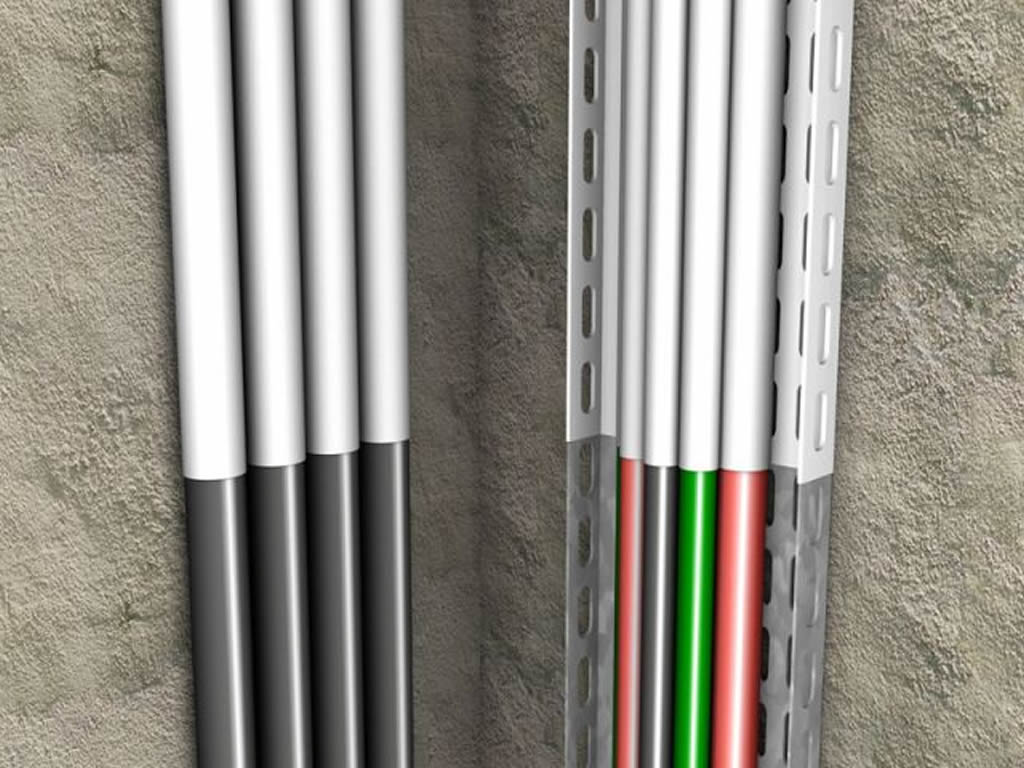

Electrical fires are fires involving potentially energised electrical equipment. The US system designates these “Class C”; the European/Australian system designates them “Class E”. This sort of fire may be caused by, for example, short-circuiting machinery or overloaded electrical cables. These fires can be a severe hazard to firefighters using water or other conductive agents: Electricity may be conducted from the fire, through water, the firefighter’s body, and then earth. Electrical shocks have caused many firefighter deaths.

Electrical fire may be fought in the same way as an ordinary combustible fire, but water, foam, and other conductive agents are not to be used. While the fire is, or could possibly be electrically energised, it can be fought with any extinguishing agent rated for electrical fire. Carbon dioxide and dry chemical powder extinguishers such as PKP are especially suited to extinguishing this sort of fire. Once electricity is shut off to the equipment involved, it will generally become an ordinary combustible fire.

Metal

Certain metals are flammable or combustible. Fires involving such are designated “Class D” in both systems. Examples of such metals include sodium, titanium, magnesium, potassium, steel, uranium, lithium, plutonium, and calcium. Magnesium and titanium fires are common, and 2006-7 saw the recall of laptop computer models containing lithium batteries susceptible to spontaneous ignition. When one of these combustible metals ignites, it can easily and rapidly spread to surrounding ordinary combustible materials.

With the exception of the metals that burn in contact with air or water (for example, sodium), masses of combustible metals do not represent unusual fire risks because they have the ability to conduct heat away from hot spots so efficiently that the heat of combustion cannot be maintained – this means that it will require a lot of heat to ignite a mass of combustible metal. Generally, metal fire risks exist when sawdust, machine shavings and other metal ‘fines’ are present. Generally, these fires can be ignited by the same types of ignition sources that would start other common fires.

Water and other common firefighting materials can excite metal fires and make them worse. The NFPA recommends that metal fires be fought with ‘dry powder’ extinguishing agents. Dry Powder agents work by smothering and heat absorption. The most common of these agents are sodium chloride granules and graphite powder. In recent years powdered copper has also come into use.

Some extinguishers are labeled as containing dry chemical extinguishing agents. This may be confused with dry powder. The two are not the same. Using one of these extinguishers in error, in place of dry powder, can be ineffective or actually increase the intensity of a metal fire.

Metal fires represent a unique hazard because people are often not aware of the characteristics of these fires and are not properly prepared to fight them. Therefore, even a small metal fire can spread and become a larger fire in the surrounding ordinary combustible materials.

Cooking oil

Laboratory simulation of a chip pan fire: a beaker containing wax is heated until it catches fire. A small amount of water is then poured into the beaker. The water sinks to the bottom and vaporises instantly, ejecting a plume of burning liquid wax into the air.

Fires that involve cooking oils or fats are designated “Class K” under the US system, and “Class F” under the European/Australiasian systems. Though such files are technically a subclass of the flammable liquid/gas class, the special characteristics of these types of fires are considered important enough to recognize separately. Saponification can be used to extinguish such fires. Appropriate fire extinguishers may also have hoods over them that help extinguish the fire.